double bind

2022

PERFORMANCE, INSTALLATION, DIMENSION VARIABLE

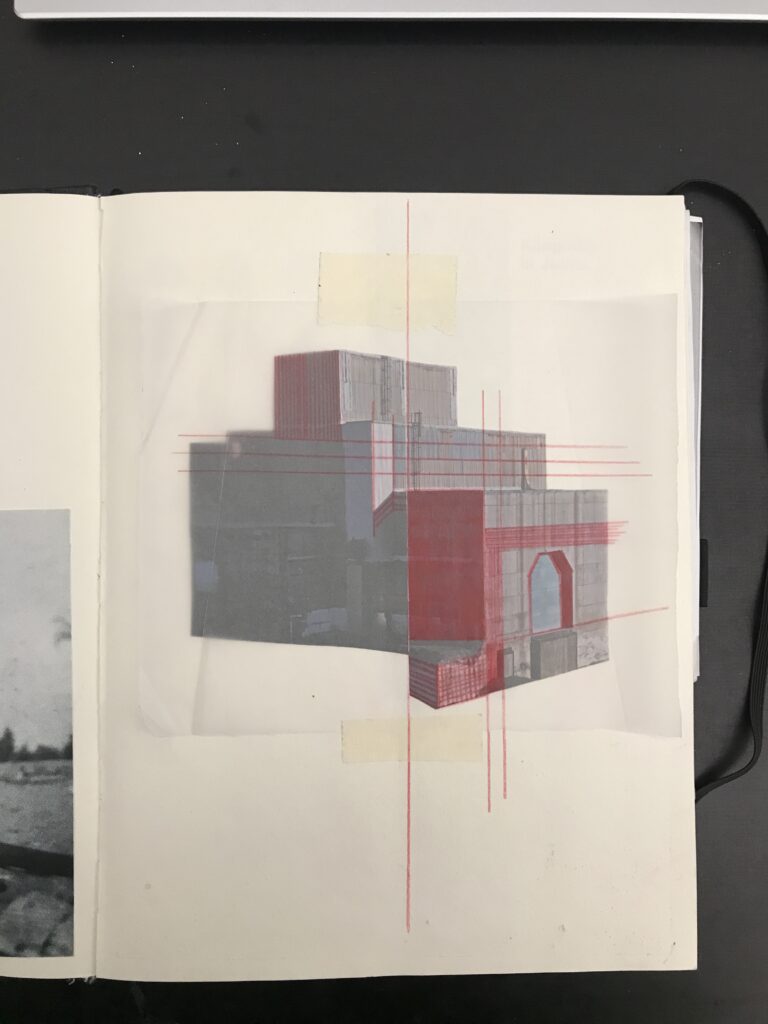

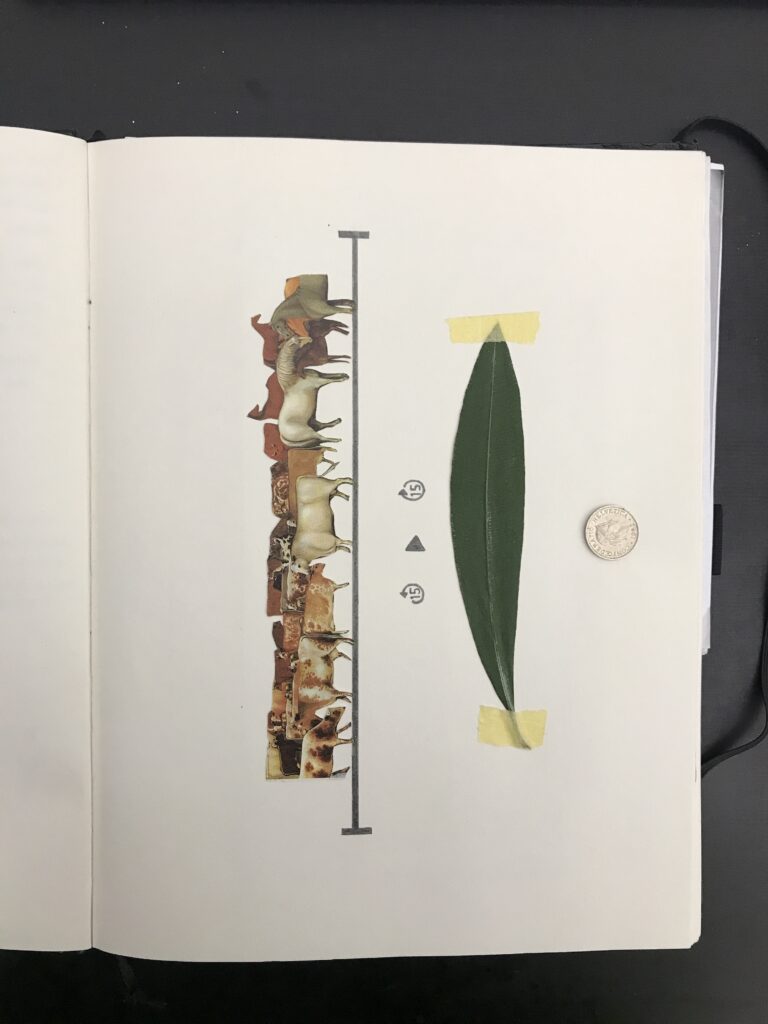

Container G-137, Two chairs that can be seated, one chair that cannot be seated, two connected curtains, one leg of the table, five tape recorders, four cassette tapes, rice, wrapping paper, double mattress cover, documents, women, voices

ウィーン中心部から電車で30分。そこからバスに乗って20分。たどり着くのは大きな門と無数の監視カメラに守られたコンテナボックスが立ち並ぶ工場地帯。手元に置いておけなくなった様々な事情を抱えたものが収まるコンテナたち。本来はAからBへと移動するためのその物体は、全ての機能を停止してそこに佇む。

「あの、わたし、コンテナを貸りたいんです。作品を見せるのに人を呼んでもいいですか?」

「モノを飾るんですよね?」

「はい、わたしとモノを飾ります」

「えぇ、問題ありませんよ」

約束通り、「わたし」と「わたしというモノ」と「モノ」がひしめき合う。二つのカーテンで区切られたコンテナ。カーテンの開口部は「わたし」と同じ背丈です。何で2つかって?裁判所で見たんです。カーテン二つで区切られた部屋。それから椅子が二脚。座れない椅子が一脚。手鏡、米袋、枕で眠る黒いドキュメント。カセットデッキ5台。

黒いドキュメントは「わたし」の代わりに「わたし」を証明するために毎年移民局に提出され続けた書類の束。米袋のそれぞれの重さと同じ。ほら、誕生の祝いに「生まれた時の体重の米」を贈るという日本の風習があるじゃない。生の重みと、制度が課す重みが、同じ袋のなかで重なり合うわけで。「わたし」って日本米みたいなもんなのよ、海外に出れば髪が黒い異邦人。何語を話そうが、どんな考えを持とうが、どんな未来を描こうが、わたしがアジアで生まれたことには勝らない。

響き続けるのは、カセットテープたちの声。AとBは、エルフリーデ・イェリネクが福島を題材に書いた戯曲『光のない。』を私自身が改訂したテキストを掛け合う。Cは日本の時報を刻み、それは同じ境遇を生きる人にしか聞き取れない合図である。私がウィーンに居ながら無意識に刻む「日本の時間」が、二つの空間を重ね合わせる。福島というテーマは、2011年以降、海外で必ず問われる「私たち」の代名詞となった。彼らは最後の審判を待つ。わたしは?

カセットデッキDは、このすべてを録音し続ける。最初の戯曲が終わると、次にはその最初の録音が再生される。2度目のそれをまたDは録音する。録音が重ねられ、訪れる人の足音や雑音が混じり込み、最後には言葉は意味を失い、空間そのものをただ記録するノイズへと変わる。この空間がカセットという物質にアーカイブされていく。

監視カメラは人を追いながらも、保管されたモノには目を向けない。オブジェクト化された身体は視線をすり抜け、機械のリズムと反復に囚われる。こうして、オリエンタリズムが作り出す「私たち」と「私」のあいだの亀裂が、空間そのものに刻み込まれていく。

パフォーマンスとインスタレーションが交わる空間で、私という身体の「境界」を浮かび上がらせる。

Thirty minutes by train from the center of Vienna, then another twenty minutes by bus.

What you reach is an industrial zone, where container boxes stand in rows, guarded by a large gate and countless surveillance cameras.

Containers that hold things which, for various reasons, can no longer be kept close at hand.

Objects meant to travel from A to B, now stripped of all function, simply standing still.

“Excuse me, I’d like to rent a container.

Would it be alright if I invited people to see my work there?”

“You mean you want to display objects?”

“Yes, I want to display myself and objects.”

“Well then, no problem.”

As promised, “I,” “the thing called me,” and “the objects” crowd together.

The container is divided by two curtains. Their openings are exactly my height.

Why two? Because I saw it once in court: a room split by two curtains.

And then: two chairs, one chair you cannot sit on, a hand mirror, sacks of rice, black documents sleeping on pillows, five cassette decks.

The black documents are stacks of papers, submitted year after year to the immigration office to prove “me” in place of myself.

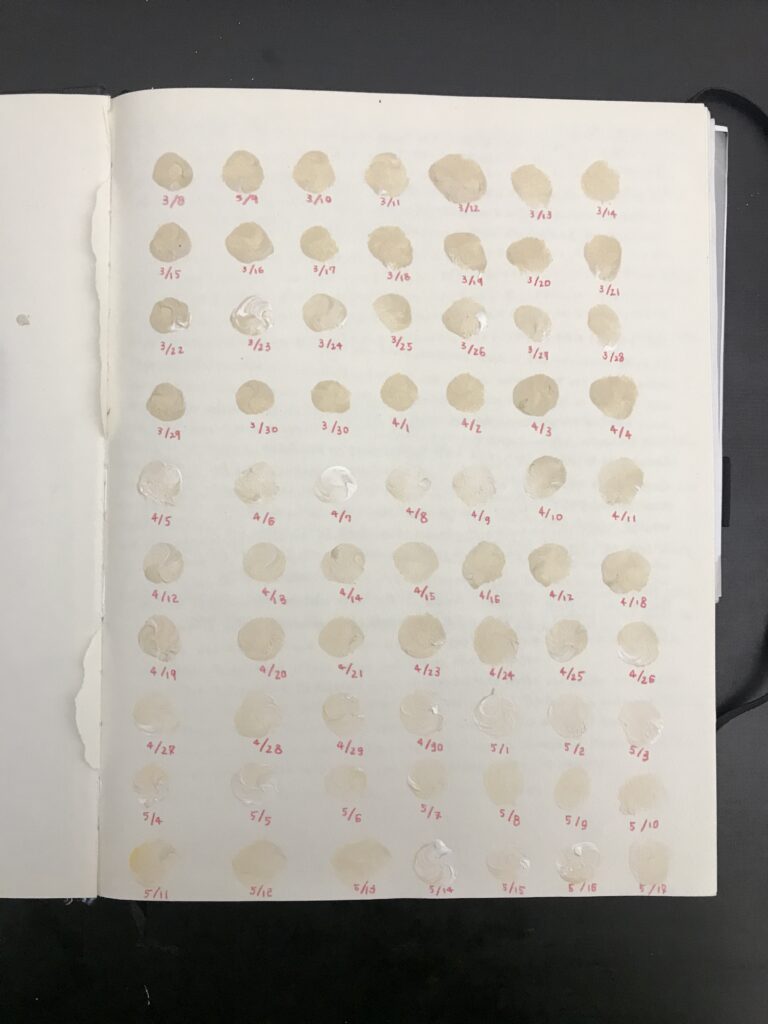

Each bundle weighs the same as a sack of rice.

You know the Japanese custom of gifting rice equal to the weight of a newborn child?

Here, the weight of life overlaps with the weight imposed by the system.

“I” am like Japanese rice—abroad, a black-haired stranger.

No matter what language I speak, what thoughts I hold, what futures I imagine, it can never outweigh the fact that I was born in Asia.

The voices of the cassette tapes echo through the space.

A and B recite my adapted version of Elfriede Jelinek’s play Kein Licht., written in response to Fukushima.

C broadcasts Japanese time signals—audible only to those living in the same condition as myself.

Even while in Vienna, I unwittingly inscribe “Japanese time,” layering one place upon another.

Since 2011, Fukushima has been one of the unavoidable questions abroad, a synonym for “us.”

They await the Last Judgment. And I?

Cassette deck D records it all.

After the first play ends, only that recording is played back, then recorded again.

Each repetition adds another layer: footsteps, noises of visitors, fragments of presence.

Words lose their meaning, dissolving into noise that archives not language but the space itself, inscribed on magnetic tape.

The surveillance cameras follow people but never the objects they store.

Once objectified, the body slips beyond the gaze, caught only in mechanical rhythm and repetition.

In this way, the fracture between “I” and “we,” born of Orientalism, is etched into space itself.

A space where performance and installation converge,

where the borderlines of my body are laid bare.

Dreißig Minuten mit dem Zug vom Wiener Zentrum, dann zwanzig Minuten mit dem Bus.

Dort erreicht man ein Industriegebiet, wo Containerboxen in Reihen stehen, bewacht von einem großen Tor und unzähligen Überwachungskameras.

Container, die Dinge aufnehmen, die man aus verschiedenen Gründen nicht mehr bei sich behalten kann.

Dinge, die eigentlich von A nach B reisen sollten, stehen nun still, aller Funktionen beraubt.

„Entschuldigung, ich möchte einen Container mieten.

Darf ich dort Menschen einladen, meine Arbeit zu sehen?“„Sie wollen Dinge ausstellen, richtig?“

„Ja, ich möchte mich und Dinge ausstellen.“

„Nun, das ist kein Problem.“

Wie versprochen, drängen sich „ich“, „das Ding, das ich bin“ und „die Dinge“ zusammen.

Der Container ist durch zwei Vorhänge geteilt. Ihre Öffnungen haben genau meine Körpergröße.

Warum zwei? Ich habe es im Gericht gesehen: ein Raum, geteilt durch zwei Vorhänge.

Und dann: zwei Stühle, ein Stuhl, auf dem man nicht sitzen kann, ein Handspiegel, Reissäcke, schwarze Dokumente, die auf Kissen schlafen, fünf Kassettenrekorder.

Die schwarzen Dokumente sind Stapel von Papieren, Jahr für Jahr bei der Migrationsbehörde eingereicht, um „mich“ an meiner Stelle zu beweisen.

Jeder Stapel wiegt so viel wie ein Sack Reis.

Es gibt in Japan den Brauch, zur Geburt Säcke mit Reis im Geburtsgewicht des Kindes zu verschenken.

Hier überlagert sich das Gewicht des Lebens mit dem Gewicht des Systems.

„Ich“ bin wie japanischer Reis – im Ausland eine fremde, schwarzhaarige Gestalt.

Egal, welche Sprache ich spreche, welche Gedanken ich trage, welche Zukunft ich entwerfe – es wiegt nie schwerer als die Tatsache, dass ich in Asien geboren wurde.

Die Stimmen der Kassetten hallen durch den Raum.

A und B sprechen meine Bearbeitung von Elfriede Jelineks Stück Kein Licht., das Fukushima thematisiert.

C sendet japanische Zeitsignale – hörbar nur für jene, die dasselbe Schicksal teilen.

So schreibe ich, selbst in Wien, unbewusst „japanische Zeit“ ein, lege einen Ort über den anderen.

Seit 2011 ist Fukushima eine der unausweichlichen Fragen im Ausland, ein Synonym für „uns.“

Sie erwarten das Jüngste Gericht. Und ich?

Kassettenrekorder D nimmt alles auf.

Nach dem Ende der ersten Aufführung wird nur die Aufnahme abgespielt – und erneut aufgezeichnet.

Mit jeder Wiederholung mischen sich Schritte, Geräusche der Besucher:innen, Fragmente der Gegenwart hinein.

Die Worte verlieren ihre Bedeutung, verwandeln sich in Rauschen, das nicht Sprache, sondern den Raum selbst archiviert – auf Magnetband eingeschrieben.

Die Überwachungskameras verfolgen Menschen, niemals jedoch die Objekte.

Sobald der Körper zum Objekt wird, entzieht er sich dem Blick, gefangen in mechanischem Rhythmus und Wiederholung.

So gräbt sich der Bruch zwischen „ich“ und „wir,“ den der Orientalismus hervorbringt, in den Raum selbst ein.

Ein Raum, in dem Performance und Installation sich verschränken,

in dem die Grenzen meines Körpers sichtbar werden.

注意:カセットテープの音声から耳鳴りのような不協音がします。イヤフォンを着けて視聴しないでください。

Note: The audio contains a discordant noise, similar to tinnitus, caused by the cassette tape. Please do not listen with earphones.

Abstract / JP

わたしの身体はしばしば、紙よりも軽くなります。

わたしの黒い髪の毛は、わたしという内実よりもわたしを定義づけます。

わたしがここ、ウィーンで暮らすには、わたしはここに暮らしていも良い人間だと、あなた方が「わたし」をこの土地の「わたしたち」として数えても安全な存在なのだと証明しなければなりません。

どのように証明されるのでしょうか?

例えば、わたしが毎日ドイツ語を話し、この社会に最大限溶け込んでいるという行いでしょうか。

いいえ。

誰も今のわたしの事には興味はありません。

わたしの未来にも、興味はありません。

わたしの今と未来は、わたしが置いてきた全ての過去が記された紙の束より重要ではありません。

ここにいるわたしは500gよりも重たいけれど軽いのです。

私の身体がここにあるかは誰も確認しませんが、ここに有効な紙があればいいのです。

わたしの身体が存在しない母国ではすべての時間の経過は、わたしの歴史として勝手に刻まれて行きます。

日本の友人や家族とオンラインで繋がれば、彼らはわたしを「わたしたち」として今もなお数えています。

ウィーンにいる「わたしも」

日本にいる「わたしも」

わたしの身体は必要ないようです。

わたしはどこにいるのでしょうか。

ここでは、要求された紙を提出すると、毎年将来1年間の存在を許されます。わたしは毎年500g 程度の重さで生まれるのです。だからそれと同じ重さのお米で、わたしはわたしを祝うことにしました。

この、A でもないB でもない地点に佇むコンテナの中で。

そしてあなたがこのコンテナに訪れる足音と、降り注ぐ雨と雪の音を常にテープレコーダーで録音します。

コンテナの中ではテープレコーダーAさんとBさんがある審判について話しています。テープレコーダーCさんはコンテナを勝手に出たり入ったりするわたしの幽霊がいる日本の現在時刻を時報として伝えます。もちろん、日本語で。だってここウィーンに住む人には関係ありませんから。テープレコーダーD さんはそれを常に監視し、録音しています。A さんとB さんとC さんの話が終わると、録音していたD さんは過去を再生します。それを今度はテープレコーダーE さんが常に監視し、録音し、再生します。すると今度はC さんがまたそれを録音し再生します。すると今度はそれをE さんが録音し、再生します。

言葉は宙を舞い、最後にはこの空間の中で再生され続けた歴史だけを鳴らします。最初にカセットテープを鳴らしたわたし以外に、全てを知る人はいませんが、わたしもまた、このコンテナで誰が何をしていたのか知りません。

コンテナの中に何があるかなんて誰も知りもしない。

歴史と紙さえあれば

海を越えられるんですよ。

わたしみたいにね。

Abstract / EN

My body often becomes lighter than paper.

My black hair defines me more than my very essence does.

To live here, in Vienna, I must prove that I am a human permitted to dwell in this place—that you can safely count “me” among the “we” of this land.

But how can such proof be made?

By speaking German every day, by dissolving myself as fully as possible into this society?

mmm…….No.

No one is interested in who I am now, where I am now.

No one is interested in who I may become.

My present and my future matter less than the stack of papers where all my pasts have been inscribed.

Here, I weigh more than 500 grams, yet I remain light.

No one checks for the presence of my body. It is enough if the valid papers are here.

In my homeland, where my body does not exist, the passage of time inscribes itself freely as my history.

When I connect online with friends and family in Japan, they continue to count me among their “we.”

The “I” in Vienna.

The “I” in Japan.

It seems my body is not necessary.

So—where am I?

Here, when I submit the papers that are required, I am granted the right to exist for one more year. Each year, I am reborn with a weight of about 500 grams. And so, I chose to celebrate myself with the same weight in rice.

Inside this container, which stands in neither place A nor place B.

And I record, with a tape recorder, the footsteps of those who visit this container, along with the rain and the snow falling upon it.

Within the container, Tape Recorder A and Tape Recorder B speak of a certain judgment. Tape Recorder C announces the current time in Japan—as if marking the hours of a ghost who slips in and out of the container at will. Naturally, in Japanese. After all, it matters nothing to those living here in Vienna. Tape Recorder D monitors and records all of this. When the voices of A and B and C fall silent, D plays the past back again. Then Tape Recorder E monitors it, records it, and replays it. And again, C records and replays. And again, E records and replays.

Words spin through the air until, at last, only the history of sounds repeated in this space continues to resound. No one but myself, who first set a cassette to play, can know everything. Yet even I do not know what has transpired within this container.

No one can know what lies inside the container.

As long as there is history and paper—

you can cross the sea.

Just as I did.

Trailer…..